Though originally identified as a type of long-horned beetle, Pulchritudo attenboroughi belongs to the frog-legged beetle group. (Image credit: Denver Museum of Nature and Science)

A beetle that lived about 49 million years ago is so well-preserved that the insect looks like it could spread its strikingly patterned wing coverings and fly away. That is, if it weren’t squashed and fossilized.

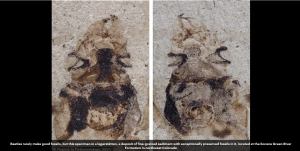

Wing cases, or elytra, are one of the sturdiest parts of a beetle’s exoskeleton, but even so, this level of color contrast and clarity in a fossil is exceptionally rare, scientists recently reported.

The beautiful design on the ancient beetle’s elytra prompted researchers to name it Pulchritudo attenboroughi, or Attenborough’s Beauty, after famed naturalist and television host Sir David Attenborough. They wrote in a new study that the pattern is “the most perfectly preserved pigment-based colouration known in fossil beetles.”

When the researchers described the beetle beauty, it was already in the collection of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (DMNS) in Colorado, where it had been on display since it was identified in 1995. Paleontologists found the fossil that year in the Green River Formation; once a group of lakes, this rich fossil site spans Colorado, Wyoming and Utah, and dates to the Eocene epoch (55.8 million to 33.9 million years ago).

Scientists initially classified the fossil as a long-horned beetle in the Cerambycidae genus. But while its body shape resembled those of long-horned beetles, its hind limbs were unusually short and beefy, which led the museum’s senior curator of entomology — Frank-Thorsten Krell, lead author of the new study — to question if the beetle might belong to a different group.

In the study, the authors described the beetle as a new genus in a subfamily known for its robust and powerful hind legs: frog-legged leaf beetles. The fossilized insect, a female, is only the second example of a frog-legged leaf beetle to be found in North America, Krell told Live Science in an email (no modern beetles in this group live in North America today, according to the study). On P. attenboroughi‘s back, dark and symmetrical circular patterns stand out in sharp contrast against a light background. This suggests that bold patterns were present in beetles at least 50 million years ago, the researchers reported.

Digital reconstruction of Pulchritudo attenboroughi. (Image credit: Denver Museum of Nature and Science)

For a beetle to fossilize as well as this one did, “you need a very fine-grained sediment,” Krell said. Silt or clay at the bottom of a lake is the best substrate for fossilizing insects, and the beetle must sink quickly into the silty lake bottom before its body disintegrates. “And then it should not rot, so an oxygen-poor environment on the lake floor is helpful,” he said.

However, questions still remain about how sediments in the lake bottom preserved the beetle’s high-contrast colors so vividly, Krell added. Visitors to the DMNS can admire P. attenboroughi for themselves, as the renamed fossil is back on display in the museum’s “Prehistoric Journey” exhibit, representatives said in a statement.