The research team presented the results of the scans last week in the Spanish capital: two of the Egyptian mummies donated to MAN in 1887 were found to be women between the ages of 25 and 40, one of whom was pregnant. The third Egyptian mummy, donated in 1925 and known as Nespamedu, turned out to be a male aged around 50 who was doctor to the pharaoh and priest to the high priest Imhotep in the 27th century BC.

Meanwhile, the Guanche mummified body that was brought from Santa Cruz, Tenerife in 1864 was different in several respects. “Although they share similarities, the main difference is that the Egyptians took out the brains and the internal organs while the Guanches left the organs intact,” explains radiologist Silvia Badillo.

The Egyptians took out the brains and organs; the Guanches left them intact Silvia Badillo, radiologist

The mummies were transferred to the hospital on June 5, 2016. Dressed in protective clothing, gloves and masks, MAN Director Andrés Carretero and his team wrapped the four bodies up and sent them off in a truck via the smoothest route.

Once safely at the hospital, thousands of high-resolution anatomical images reconstructed the bodies in 3D, with surprising results.

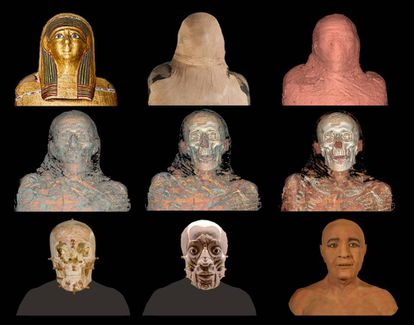

Hidden amid Nespamedu’s bandages the team found nine accessories, including a necklace, bracelets, diadem and sandals, and 16 amulets. “There was something on his forehead that all the archaeologists agreed was a diadem,” says radio-diagnostic specialist Javier Carrascoso, who added: “It was amazing to be able to see the face of a mummy preserved more than 2,000 years ago.”

The Scarab on the diadem – “the symbol of resurrection” – and images depicting Horus’s sons and the god Thoth on other objects were also present in the mummies’ outer casing, allowing researchers to determine that Nespamedu was the doctor and priest mentioned in the writings found in the bandages.

As well as bones, researchers were surprised to find fragments of ligaments, tendons, muscles, and the heart in the Nespamedu mummy, even though it had had its internal organs removed.

“They would leave the heart because they believed that was where the essence of being and feelings were,” explained Vicente Martínez de Vega, head of the department of Diagnostic Imaging, who says the 3D reconstruction of the bodies was key to confirming their high social status, while also allowing a forensic sculptor to give shape to the real face of the mummy.

Nespamedu, who lived in the Ptolemaic period (300-200 BC), “was a doctor who practiced his profession in the temple of Imhotep, where he cured pilgrims,” says Egyptologist Marie Carmen Pérez Die, who has confirmed this was the Saqqara tomb in Egypt – clinics often existed inside the temples.

The study of the Guanche mummy has shown that mummies from the Canaries had better teeth than their Egyptian counterparts

The research has been filmed as the basis for a documentary co-produced by Spain’s state broadcaster TVE and Story Productions. “It’s difficult to explain the range of emotions we’ve experienced,” says producer Regis Francisco López, who traveled with his team to Saqqara to film. “It was like going back to the time of Nespamedu.”

The study of the Guanche mummy, who lived between the 11th and 13th century B.C. and turned up in a cave in the Herques gully in Tenerife in 1763, has shown that mummies from the Canaries had better teeth than their Egyptian counterparts.

“Dental health was bad in ancient Egypt,” says Vicente Martínez de Vega, head of the image-diagnosis department at QuirónSalud hospital, who says he found the sight of the bodies without their bandages in the scanner “unforgettable.”

“This means that the Guanche mummy had a low-sugar diet,” says his colleague Teresa Gómez Espinosa.